Can Food Be Art?On the dangers and pleasures of food as art. Words by Virginia Hartley and Matt O'Callaghan; Illustration by Sinjin LiGood morning and welcome to Vittles Season 6: Food and the Arts. A reminder of the season theme can be found here (though we are no longer accepting pitches.) All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £600 for writers (or 40p per word) and £300 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. All paid-subscribers have access to the past two years of paywalled articles. A Vittles subscription costs £5/month or £45/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing then please consider subscribing to keep it running and keep contributors paid. This will also give you access to the latest Vittles project which concluded last week - The Vittles London Pub Guide. The guide has now been republished in full, with an easy to use map of all pubs included (and some not included) here. If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or subscribe for £5 a month, please click below. CW: Some of today’s newsletter discusses disordered eating.

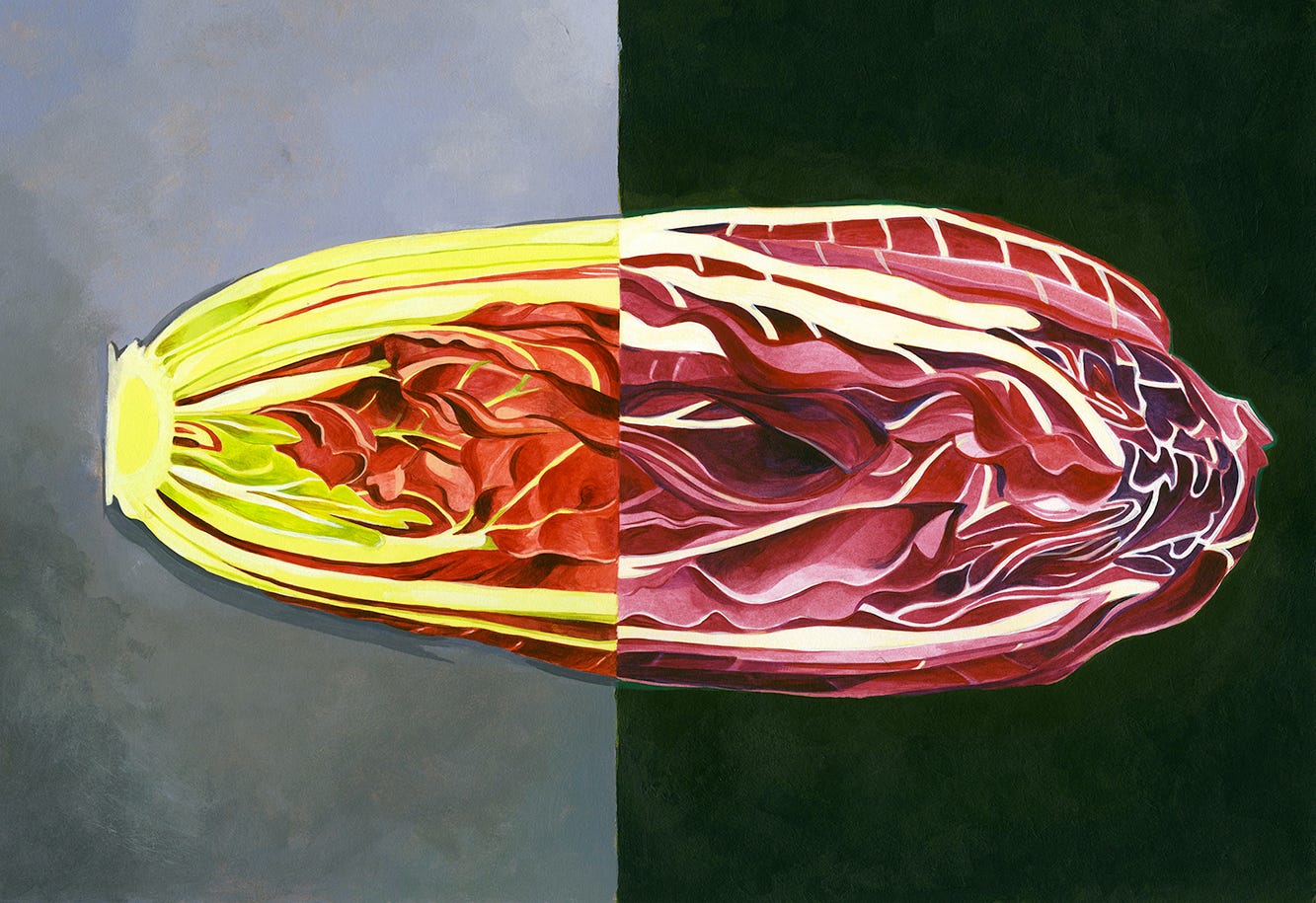

On the dangers of food as art, by Virginia HartleyEarlier this year, around Valentine’s Day, I saw an ad campaign which felt familiar. The tagline of the campaign – which told me that, rather than gifting bouquets of flowers, I should give beautiful vegetables – was illustrated by a painterly image of a radicchio displayed in a vase; the advert urged me to arrange its leaves artfully like a florist. I considered that, in its messaging, eating came after – an afterthought? – once the bouquet was no longer suitable for display and when its nutritional value had declined. The campaign’s hidden communication – that we could aestheticise our food to the point that it is no longer food, but instead becomes a means of decorating our table – disturbed me greatly. For when we say food is art, we are in danger: for many years, this was how I convinced myself it was OK not to eat. Some time ago I worked as a copywriter for that very same company, where my job was to come up with artful descriptions of exquisite produce. I had come to this job – in which I wrote about and handled (but mostly did not eat) fresh produce – because it perfectly suited the disordered relationship with food that I had been cultivating for years. All the time I was writing about food, describing it in ornate language – placing it on a pedestal – I was able to satisfy my hunger for food without putting it inside my body. My transformations were a kind of digestion, but crucially a kind which left my body outside. When I told the doctor in my eating disorder outpatient service that I worked with food, I thought she would find it strange, but instead what I remember is how unsurprised she was. In retrospect, I was clearly not the only person with an eating disorder who sought out food environments, finding a strange symbiosis there. In my copywriting role, I was taught to think about growers as artists. In some ways, this conferred on undervalued farmers a status more proportionate to their skill. Disturbingly, though, this exalting of baroque methods of farming also seemed to refuse the idea that the produce would ultimately be food. For example, the method of ‘sand-forcing’ – transplanting a single radicchio, then burying it in sand and leaving it in the dark for weeks – seemed at odds with the fact it would be harvested like any other crop: washed, ripped apart, then eaten for dinner. The noblest produce was to be appreciated raw so that, until the very moment of eating, I was preserving its perfected final form as much as possible. These artful vegetables had no need for a cook; they were already the finished work. Those days I felt frozen as the food’s audience; suspended in a submissive, uncritical state, I was unable to use my voice in the kitchen. While this had long been a feature of my eating disorder, the environment at the brand only enhanced the feeling. My preferences were stunned in favour of reverent produce worship. In the messaging I was fed – which became the messaging I wrote – the emphasis on that perfect point of ripeness, on the uncompromising harvest at dawn, told the story of a beginning which was also an end: a point beyond which the food could only decline. I remember being in the staff kitchen one day (not eating) and someone telling me the correct way to eat an old variety of tomato. I understood from this: preparing it differently, seasoning it with pepper, not salt, slicing it, not chopping it, would be to destroy the tomato. I didn’t slice my tomatoes, nor did I add pepper, because this spoke to my established illness perfectly. I was all too ready to acknowledge my food as art and play my part as custodian of its heritage. Who knew what I might do to the tomato-as-work-of-art? I might accidentally ruin it, destroying its bred-in perfection. If I cooked it, how would my heritage, saved-seed tomato be superior to an industrially grown tomato from the supermarket? I saw how emphasising the difference between these products was a priority for a brand whose products needed to remain recognisably theirs to justify the price. In their anxiety to protect beginnings – emphasising the hand of the grower, surface imperfections and irregularities as proof of originality and origin – I read a denial of the real nature of their product: something whose final collapse in the pan is inextricable from its life as food. As time went on in that role, I found I could surround myself with food that I did not have to eat. I was encouraged by individuals passionate about produce to taste morsels – so that I could convert them into seductive words – but I would never be forced to have more. In fact, should I eat too much, someone might reasonably have cause to wonder if I was doing my job: it was as if the more I was able to distil from a single grape, from one leaf of basil, the better I was doing. I became skilled at unravelling whole stories from the small circumference of a pea. I found entire plants miniaturised in a microleaf. I spent hours wrapped in the mist of vast fridges, in a state of preservation. I was like the food, which almost didn’t know it was dying, suspended between growth and decay in a state-of-the-art environment conceived to mimic the conditions of life. I convinced myself that I might – like the fruits and vegetables detached from their various root systems and branches – omnipotently survive on nothing. I spent time at my desk; I went home at the end of the day; I even turned up to my outpatient appointments – and I was not unlike a lettuce, displayed for several hours at room temperature before being returned to the fridges to be restored. When I saw the radicchio advert this spring, I viewed it with the long-distance lens of retrospect and thought about the unfortunate ways I was implicated in it. After all, it was just the kind of concept I had once fed and endorsed. Perhaps people like me had been waiting all this time to be told that you don’t always have to eat your food – you can also just look at it. Certainly, some natural order had been disturbed – if food becomes ornamental, then the question is not just about what happens to the displaced ornament (in this case, the flowers formerly in the vase) and the livelihoods associated with its production. The question also remains: What is left behind in place of food at the table? The answer for me those years ago was often, literally, nothing. I composed a plate of food, but I barely ate it. I made dinner and then transferred most of it to the fridge, because I had come to regard eating as a form of destruction. As such, I had conferred to my plate a kind of talismanic value: something which protected me from the world, and from life, only as long as it remained untouched. Once I began to recover and returned food to its place at the table, in many ways I ‘won’; but I also found it hard to let go of the private, symbolic world I had cultivated around food. When food was art, I attempted to protect myself from loss by making it last forever, and I feel that the still-life painting understands some of this impulse to preserve. Perhaps that’s why this style – which is often regarded as the ‘lowest’ of the artistic genres – remains the most commercial: the one we still want, which we still put on Instagram; on our walls. The brand’s ad campaign drew this knowledge into its commercial orbit and gave an unspoken justification for why one might view food as a luxury product, something to desire in a way which goes beyond feeding a hunger. As such, we become collectors, not cooks. If we simply cooked the radicchio in the privacy of our kitchens, wilting it down in a pan until it lost its colour and structural integrity, until it tasted good and nourishing (all the while resisting taking a picture), and then, through the act of eating, effectively erased it as if it had never been there, then the whole food-as-art industry would collapse. Because who ever brought a Cézanne still life and, once having done so, ate it for dinner? Far better to buy oranges instead. These days, I remember the other name for the still life, which is the French term for these inedible banquets, those purely ornamental fruit bowls, that only-ever-Trompe-l'œil garden produce. Rather than emphasise the life, the French notice the death – and perhaps the deathliness of the impulse behind them, of our appetite for them – and call them not still life but nature morte. On the pleasures of food as art, by Matt O’CallaghanNature gave us chicory, but it was the gardener who, making it beautiful, gave us radicchio. At some point in its very long history, Cichorium intybus – a run-of-the-mill, dandelion-esque bitter leaf – underwent a metamorphosis, shunning mundane greenery for leaves of intense reds and purples held together and offset by marble-white ribs and, finally, cicoria became radicchio. While, visually, the two are very different species, in actual fact they are almost genetically identical (like a wolf which has evolved into a domestic poodle). The red did exist in the original cicoria – a faint stain on the vein that ran up the centre of each plant’s leaf, distinguishing them from dandelions – but what was then merely a hint of red has been seized upon by generations of growers and breeders hell-bent on improvement and refinement. It is the abundance of red that turns a cicoria into a radicchio, from a vegetable into a diva, and, through generations of aesthetically minded gardeners creatively intervening to beautify a weed, radicchio has been transformed into a family of Best in Shows. And this is where art (or science or magic or whatever you want to call it) comes into play. The red in radicchio is triggered by a type of photosynthetic pigment that is more efficient than chlorophyll at absorbing energy in falling light levels. As winter approaches, radicchio makes the best of things by blushing red and purple, prolonging its growing season. For radicchio to be produced commercially, it must be grown in darkened sheds, with its roots submerged in flowing spring water to keep its temperature at around 10 degrees centigrade. Starved of light (to intensify the red pigments) but dangled in a relatively warm bath, our huddled radicchi begin to grow anew inside their overcoat of last season’s leaves. The crop is ready within a few weeks, and skilled hands peel away the old leaves, trimming and paring roots to a standardised length and transforming a bedraggled vegetable into a polished thing of beauty, with almost frond-like curls of intense radicchio red and ribs a bright bleached white. Radicchio fan sites (oh yes, there are many) have all sorts of unsubstantiated origin stories about the first humans to develop this technique, with claims that radicchio was first cultivated in the fifteenth century. The closest I’ve come to proving this for myself is through a painting by the sixteenth-century Flemish artist Joachim Beuckelaer; his scene of women selling vegetables (‘The Four Elements: Earth’) includes, just left of centre, some characteristically trimmed leafy vegetables, which at least proves that this particular technique was being used at the time, even though Beuckalaer’s vegetables are probably just endive. Another legend claimed that, in the nineteenth century, visiting Belgian gardener Francesco van den Borre realised that he could apply the technique used for blanching and forcing endive to the radicchi he saw in Treviso (though his son later debunked this myth). Whatever the case, it hadn’t become mainstream enough to get a mention in Pellegrino Artusi’s encyclopaedic Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well (1891), the ‘first’ recipe book of the newly united Italy, while Ada Boni has just one recipe for an insalata di radicchio in her 1929 bible of Italian cooking, Il talismano della felicità. Whenever the radicchio that so enchanted its growers first appeared, what is known is that the local climate, fertile soils and abundant spring waters of the Po valley combined to make this new vegetable very much at home, and soon it had become localised, leading to the creation of the elongated Radicchio di Treviso Tardivo. There are three other certificated varieties with this protected status, or ‘Indicazione Geografica Protetta’ (IGP), each with their own aesthetics. In Chioggia, you can find the palla rossa, or ‘red ball’ – a squeaky, glossily dense globe. Verona is a cross between the torpedo of Treviso and the football of Chioggia, its bone-white veins far more prominent than either of the other varieties. My favourite is Variegato di Castelfranco, bred from a cross between the original red radicchio and the looser, floppier escarole. In appearance, it is more lettuce-like and, rather than being dominated by red pigments, the lack of light sees it becoming a pale, almost ghostly white version of itself, with freckles of reds and pinks that fade to oblivion in its heart. And these are just the certified, enshrined versions of radicchio; there’s also a relative newbie – a stunning pink variety called ‘la rosa del Veneto’ – bringing added camp to the salad drawer, as well as Grumolo Rosso, a Veronese joke because it’s red, and looks like a rose, and is sold in bouquets for Valentine’s Day by enterprising grocers. I discovered radicchi as art by growing them myself – not in Veneto, but in Birmingham (which may have more canals than Venice, but certainly doesn’t have the spring waters of the Po valley). For me, they are one of the most satisfying types of vegetable to grow. Squash are fun because of their fecundity; tomatoes are a challenge because of their desire, like sheep, to find ways to sicken and die. But radicchio offers me an opportunity to wrest something out of its designated comfort zone and persuade it to flourish anyway. The seeds are sown in the early summer, requiring strict labelling, as all varieties of radicchio and cicoria begin life looking like identical siblings: small, green and ovoid leaves. Throughout July and August, they race to beef up, mostly refusing to hint their primary purpose. Not until September do they start to flush with colour and begin their various transformations – hearting up to become a ball; elongating to become a torpedo – and as the days shorten and the temperatures drop, they start to dress for their parade. There are few things that match the joy of harvesting a fresh radicchio in winter dusk – stripping off frosted, damaged outer leaves to release the stab of purple red or the chaotic speckling of greens, pinks and reds. In that moment, you are taking part in a performance that has developed over millennia, from the moment the first bitter leaf was picked, through the many nameless growers who selected the following year’s seed based on a slightly stronger red, a slightly more pleasing form. So what is it that elevates this ennobled salad to an art form? It’s not just because of the apocryphal radicchio tale, of a woman who adored Variegato di Castelfranco so much that she not only decorated her home with heads of it, but even took to wearing one as a hat to a party. (I want this to be true more than I can express.) It’s that I believe this leaf, more so than any other vegetable or fruit, has a dualistic existence as art and food. Radicchio has two purposes which are mutually incompatible: decades and centuries of development, months of growing to produce a peacock of a plant, a living work of art… which instantaneously loses its looks when its second and final purpose, as food, is realised. As soon as you cook radicchio, all of its aesthetic qualities vanish: the colours muddy, the leaves slump, and it becomes no more or less enticing than spinach or chard. From then on, it is purely flavour – bitter, sweet – even though everything about radicchio up until the cooking is about appearance and process. It reminds me of an artist’s show for a gallery I worked at years ago. They spent weeks making keys out of ice in the freezers of the nearby Tescos, talking to the customers and staff about what they were doing and why. Freezers broke; keys defrosted and were remade; people were both bemused and enchanted. And then, one evening, all those keys were deliberately set afloat in the canals of Birmingham. As they melted, the art disappeared. The whole show, it turned out, was about the process that led to its disappearance. Food is art, not just in its cooking and appearance, but in the processes and stories that are attached to it. Radicchio encompasses all of these. It is not just a handsome addition to the salad drawer, but it also brings along fun, surreality and hints of obsession. When I grow, harvest and cook radicchio, I am involved in a process of creation, nurture and destruction akin to, if not as dramatic as, The KLF burning a million quid, or as emblematic as the self-shredding Banksy. And besides, when I finally wear one as a hat, I shall make sure there is photographic evidence, which I will frame and hang on the wall. Credits

You're currently a free subscriber to Vittles . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |