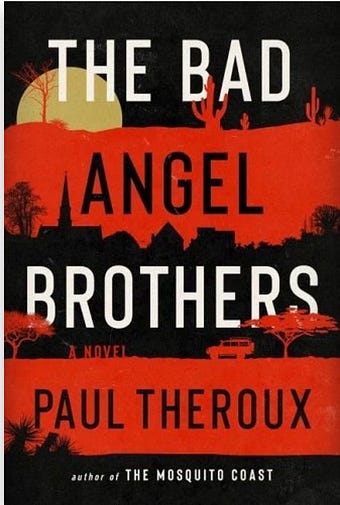

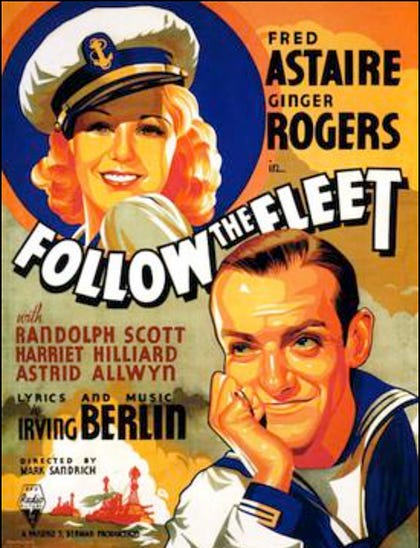

You are reveling in CultureWag, the best newsletter in the universe, edited by JD Heyman and written by The Avengers of Talent. We lead the conversation about culture: high, medium and deliciously low. Drop us a line about about any old thing, but especially what you want more of, at jdheyman@culturewag.com “If you aren’t reading the Wag, you’ll never get anywhere when it comes to quantum electrodynamics.” —Richard Feynman Happy Labor Day Weekend, Wags!The End of the Office, Rings of Power, Paul Theroux, Julia Jacklin, and More ...Dear Wags, This Labor Day weekend, let’s discuss the value of your work. Nobody pays this any mind, but the last holiday of summer was established in 1894 as a sop to ascendant trade unions. It’s the product of a shift to an industrial economy, and the surliness of those compelled to toil in it. So, before you sip that Mai Tai, toast the evolution of the relationship between labor and capital—from one punctuated by street brawls to a coöperative arrangement that allows for a few days off. For all sorts of diabolical reasons, this compact is fraying. Wag Emerita Barbara Ehrenreich, who died on Sept. 2, could innumerate the reasons why. Things have gone sour at the home office, and companies are having a devil of a time luring obstreperous employees back. This is odd in America, which has always made a fetish of work. We have a long tendency to confuse what we do with who we are, and are less likely to see ourselves as members of a seething proletariat than a hodgepodge of moguls-in-waiting. An American who uses the term working class is quite unlikely to be a working-class American. This is will be a disappointment to Shark Tank fans, but flipping the man the bird and working for oneself is not the liberation hyped. Self-employment has been romanticized, but being a drone for a faceless mega-corporation had a better health plan. In its heyday, mass employment provided workers with all sorts of bennies, not least of which was the friendship of other human beings. That way of working has been eroding for some time, and it’s making those still employed by big companies awfully cranky. They are angry at the hierarchy not because they long for a Socialist revolution but because it is becoming ever harder to climb the ladder. We snarl at the entitlement of others because we all feel entitled to far more than we are getting. This dissatisfaction is manifesting itself in very American ways. The organizational meltdown of the last five years or so — the willingness of many white-collar employees, particularly younger ones, to discard sensible professional behavior in favor of open rebellion against their managers—has many mothers. Americans of all ages are snowflakes when it comes to work. Our cult of individualism makes it very hard for us to believe that we will not, like Tess in Working Girl, end up running the whole shebang at the end of the movie. When we feel thwarted, look out. The changing nature of work has led not to collective industrial action but a million little guerilla wars — complaints and lawsuits, firings, and an anarchic atmosphere of carping and dread. Old notions of how to comport oneself professionally (nobody gets to tell anybody how to dress anymore, but everybody has a say in how we think) are out the window. Wholesale attempts by American companies to imitate tech firms (open plan offices, Slack!) without tech-sized paychecks haven’t been popular. All the bromides of business culture (coaching for success, giving good feedback, team-building) are no match for a tidal wave of disaffection. Little wonder so many people are declaring they’re quitting. Perhaps a million little cottage industries are about to bloom in their wake. Then again, a future in which most people aren’t conventionally employed — due to A.I., Armageddon, or whatever—adds up to a whole lot of people looking for trouble. Sure, they could turn their attention to dismantling systems of oppression, but it's just as likely they’ll rain hellfire down on one another. Judging from current events, which seems more likely? Old-fashioned work never made us entirely happy. Shame on us for giving it so much weight! But it is how we made ourselves useful. It had a way of rescuing us from the mire of the self and distracting us with projects. It could be soul-deadening, but the soul sometimes needs to be put in its place. Perhaps it helped teach us that a life expectation of boundless fun and creative fulfillment was childish. Generations of Americans put away childish things and got down to business. Here we are, at a moment with parallels with 1894. It’s a time of economic turmoil and a rising sense that nobody gets to be the boss of us. Ask people why they like working from home, and quite a few will tell you that they don’t miss all the drama at the office. But as we travel further from that benighted old place, we are beginning to appreciate how it channeled our restless energy and unhitched us in moments from the yoke of individualism. Whatever takes its place, let’s hope it reminds us that we can be part of something much bigger than ourselves. Yours Ever, Katherine Parker Well. Amazon’s Rings of Power is getting nicely received by most blue check critics, and pilloried by trolls, orcs, and balrogs online. Everybody saw this coming. Amazon spent $1 billion to produce a new series about Middle Earth, which many viewers will probably love. Presumably, the reason they did so is that millions of fans already love Middle Earth. When one adapts J.R.R. Tolkien or builds a universe inspired by his fiction, one must confront the unreasonable expectations and hidebound orthodoxies of those who (over) identify with his oeuvre. Tolkien, who died in 1973 at 81, was a product of his time. By his time, we mean World War I, a conflict that shaped him to his core. The author was an Englishman of a generation that suffered unimaginably in that crucible of horror; the Rings Saga reflects that trauma in myriad ways. Tolkien was a Roman Catholic, a traditionalist, and a professor of English and Anglo-Saxon at Oxford. His work can be enjoyed by anybody (even those who don’t self-identify as Nerds) but it’s deeply moralistic and consumed with themes of good and evil that reflect an inherent conservatism. Readers of his books may notice that female persons are almost entirely absent from them. Tolkein was devoted to his wife Edith, to whom he was married for 51 years, but he lived almost entirely in a world of men. Over the decades, some enterprising critics have also discerned a whiff of racism and antisemitism in his books. This is more of a stretch, but we write of a Victorian, born in 1892. Tolkien was weirded out by the hippies who made a hero of him in the 1960s (they used to pop up in the garden). He would surely be mystified by the hoo-hah around him now. The makers of Rings must contend with the exigencies of the present, and their Middle Earth is populated with female and nonwhite characters (perhaps we ought to say nonhuman characters with a diversity of 21st Century racial characteristics). Fundamentalists have taken umbrage because it is not the world Tolkien committed to the page in 1937. Even silly fantasies must reflect their times. In 2022, we are highly attuned to questions of identity, which can lead to intriguing reinventions and bald outrages. Future generations will busy themselves rewriting our stories. Any culture war mishegoss stirred up by Rings is a small thing next to the depth of attachment people have to the stories of childhood. Contemporary revisions to cherished narratives always meet with hostility. To meddle with these tales is to tamper with the tenderest part of the imagination. But meddling will happen — to Winnie the Pooh, The Wizard of Oz, The Chronicles of Narnia, Star Wars, and The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien couldn’t have anticipated the impact of his work, but the need of many generations to engage with it is a testament to his genius. May he always tempt us into his garden. — Lucy Pevensie FictionWag Supremo Paul Theroux has cultivated a reputation as being impossible, which is all part of his charm. His family relationships are a bit sticky: His mum was appalled by his first book, and his brother Alexander once described him as small and surly and spiteful ... He has bowel worries and eats prunes for breakfast and once made inquiries to me about platform shoes. Now, going after a sibling’s bowels is a low blow! We’re positive our Paul is not drawing from personal experience to enrich his 33rd novel, The Bad Angel Brothers, which involves Cal, who has grown up in the shadow of godawful Frank, a power lawyer who has a way of stealing everything —attention, glory, girls—that should rightfully be his. Even after he builds his own fortune in South American mining, there are many old scores to be settled. Of course, Cal wants Frank dead! See what happens when you call your brother short? — Adam Trask NonfictionThere is a raft of new books about modern American right and the evolution of the GOP from the party of Reagan to the tribe of Trump. Nicole Hemmer’s Partisans is an especially trenchant telling of that story, outlining how Pat Buchanan, Newt Gringrich, Rush Limbaugh and others helped shift the modern conservative movement’s agenda in the post-Cold War era from anticommunism to antiglobalism and deep skepticism about American democracy itself. Read it and weep. In 2015, Tom Mustill was kayaking along the California coast when a humpback whale breached near his craft, plunging him into the depths. The naturalist and filmmaker survived unharmed but became obsessed with animal communication. How to Speak Whale explores the growing body of science decoding how animal messaging, opening the possibility that we may all one day be like Dr. Doolittle. Whales, with their big brains and strange music, hold the key. —Ned Land The News Agents are Emily Maitlis, John Sopel, and Lewis Goodall, three of the UK’s sharpest journalists. Their podcast is an examination of issues confronting Britain and the world — among them inflation, the agonies of the Conservative Party, and of course, the investigations into Donald Trump. But they aren’t joining the horde of lazy people giving hot takes. The trio goes in for an in-depth analysis of complicated issues, bringing a healthy dose of humor and skepticism to the whole affair. Your troubled world has never been so much fun. —Jane Craig I was neon, I was the nearest door/I was the sign that said you've been here before. Have you ever fallen madly in love and forgotten who you were? Sydney’s Julia Jacklin sings about it in I Was Neon. The song strums along, telling the story of how she was once a little more vivid and hopeful before her heart was broken. She’s made some mistakes, but she’s likely to repeat them. Am I gonna lose myself again? Probably, but will be worth it. —Frances Houseman That Mark Sandrich’s Follow the Fleet is not the greatest of the Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers musicals says a lot about the depth of the field. It’s a bit of fluff, of course — about two former dance partners who reunite when his naval ship pulls into San Francisco. Still, the movie contains some of the best Astaire-Rogers duets of all time, most importantly, Let’s Face the Music and Dance, which Sandrich filmed in one continuous shot lasting two minutes and fifty seconds. Rogers’ dress was heavily weighted to achieve a graceful swirl when she turned, and the heavy hem hit Astaire in the face as they danced. The pair filmed the grueling routine 19 more times, but Astaire chose the original as the final take. The set, designed by Caroll Clark and Van Nest Polglase is a masterpiece of Hollywood Moderne design. It’s worth it for that one number alone. (Sept. 5, TCM). — Bilge Smith Questions for us at CultureWag? Please ping intern@culturewag.com, and we’ll get back to you in a jiffy. CultureWag celebrates culture—high, medium, and deliciously low. It’s an essential guide to the mediaverse, cutting through a cluttered landscape and serving up smart, funny recommendations to the most hooked-in audience in the galaxy. If somebody forwarded you this issue, consider it a coveted invitation and RSVP “subscribe.” You’ll be part of the smartest set in Hollywood, Gstaad, Biarritz, and the Hotel Sacher in Vienna, which still makes more than 300,000 delicious Sacher-Tortes a year. “I can resist everything except the Wag.” —Oscar Wilde You’re a free subscriber to CultureWag. For the full experience, become a paid subscriber. |